Olivas Garten has been published on 16 August 2013.

Olivas Garten has been published on 16 August 2013.The narrator, who has lived in Germany for a long time, learns one day that she has inherited an olive grove from her grandmother, in Vodice, on the eastern Adriatic coast. She knows exactly: this will be a daring adventure, a Don Quixote against the headstrong southern bureaucracy. There will be chaos, passions, laughter, tears and plenty to eat. Supported by her exemplary organised northern German husband, she sets off into the landscape of longing of her past. She immerses herself in the entrancing tales of her far-flung family. And into the cruel conflicts of a bloody century.

Oliva's Garden

The novel Oliva's Garden has been translated into Croatian and Macedonian; excerpts have been translated into English, Russian, Albanian, and Hungarian. The rights to this novel are held by Corto Literary Agency

About the novel Oliva‘s Garden

When notified by a lawyer that her grandmother Oliva has left her an olive grove on the Croatian coast, the narrator initially simply wants to ignore the letter. Her grandmother has been dead for eighteen years already, and her daughters have not even managed to agree on the fate of the family home in Vodice, which – in contradiction to the general boom in tourism – is now slowly falling into decay.

Anyway, neither the narrator’s mother, nor her sisters, nor the eldest cousin Bianka, who has grown up with them, due to losing her parents in the Second World War, seem to be particularly practically minded. Croatia is upside down, the country’s democratization seems to happen mainly in the speedy and corruption-prone privatization of the property, which the socialist state once took from its subjects – among this a piece of land, which the sisters hope to earn some money from, although a pretentious wellness resort has been created on it in the meantime. The land registry and real estate cadaster of the country are in the same mess as they have always been.

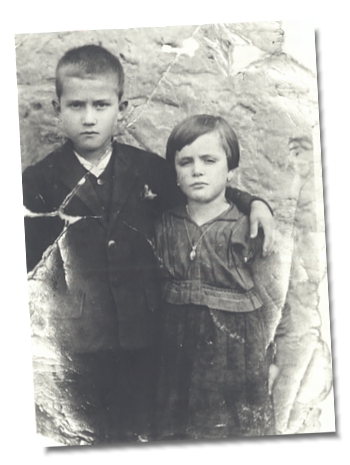

All stories of the family are leading back into the past, especially back to experiences of the Second World War, but no one has told them yet in context – not great-grandmother Paulina, because she was always busy, neither grandfather, who could find expression only in the language of his party, nor grandmother Oliva, who spent decades lying on an ottoman in the kitchen hardly uttering a word, nor the aunts, because they would have liked nothing better but to forget those years. Paulina had lost her only son, one grandson and her daughter-in-law during the war, her sister Klara, too, lost her only son, both their houses were set alight by Italian occupation forces, both of them had been detained in Italian camps and Oliva had been interned in a German one – who would like to remember all that? But then – one cannot completely block out these topics either.

All stories of the family are leading back into the past, especially back to experiences of the Second World War, but no one has told them yet in context – not great-grandmother Paulina, because she was always busy, neither grandfather, who could find expression only in the language of his party, nor grandmother Oliva, who spent decades lying on an ottoman in the kitchen hardly uttering a word, nor the aunts, because they would have liked nothing better but to forget those years. Paulina had lost her only son, one grandson and her daughter-in-law during the war, her sister Klara, too, lost her only son, both their houses were set alight by Italian occupation forces, both of them had been detained in Italian camps and Oliva had been interned in a German one – who would like to remember all that? But then – one cannot completely block out these topics either.

The narrator, in her turn, had actually wanted to forget that her family had participated actively in the anti-fascist fight, as the values forming the foundation of this political world order seemed to have vanished in the same way as had the country of Yugoslavia. Particularly in Croatia, which had been attacked by the Serbian-dominated Yugoslav People’s Army, the old antifascists seemed to have become unpopular, because they were identified with just this Yugoslavia. Even if Tito, the famous resistance leader and legendary Yugoslav president, was Croatian: his fight against the foreign occupation forces and the subsequent Socialism appeared now in the aftermath as a betrayal of Croatian independence.

The narrator, in her turn, had actually wanted to forget that her family had participated actively in the anti-fascist fight, as the values forming the foundation of this political world order seemed to have vanished in the same way as had the country of Yugoslavia. Particularly in Croatia, which had been attacked by the Serbian-dominated Yugoslav People’s Army, the old antifascists seemed to have become unpopular, because they were identified with just this Yugoslavia. Even if Tito, the famous resistance leader and legendary Yugoslav president, was Croatian: his fight against the foreign occupation forces and the subsequent Socialism appeared now in the aftermath as a betrayal of Croatian independence.

Longing for the South begins to gnaw at the narrator. She is living in Germany, she is married to a German husband, and she has rather come to accept the fact that in Northern Europe the sun shines rather less and that people know less about food, as - instead - everything is well regulated and in good order. The story of an adaptation to Germany and the simultaneous quest for origins is woven into one with the chronology of events, which have molded the family’s history: the founding of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the first national tensions in this country, which disintegrates for the first time during the Second World War, only to disintegrate again at the same breaking points at the end of the twentieth century.

The Croatian coast was the setting for three years of bitter local resistance to the fascist Italian occupation forces. Once Italy had capitulated, the German troops hurried to subjugate the coast to their power, causing an exodus of the civilian population to Italy and to Egypt, into the Sinai desert.

The Croatian coast was the setting for three years of bitter local resistance to the fascist Italian occupation forces. Once Italy had capitulated, the German troops hurried to subjugate the coast to their power, causing an exodus of the civilian population to Italy and to Egypt, into the Sinai desert.

The immersion into the hardly processed history of the country, which is closely entwined with the family history, runs parallel to the narrator’s attempt to rescue the inherited olive grove from the clutches of an obscure bureaucracy. Many meals (family relationships in the South are usually discussed at tables bursting with food) and some journeys, leading the narrator to several towns on the Croatian coast, to islands and also to Italy, are interspersed with grandmother Oliva speaking up from her ottoman again and again – not with her long since silent voice, but with her thoughts, her flow of consciousness.

Short extract from the novel

Short extract from the novel

The taste of olive oil asserted itself in my memory. I knew that the letter writer was not talking of those pale yellow, thin, virginal oils in tiny, elegant, Italian bottles, but of those vividly green, viscous, slightly bitter oils, reaching me in Germany in Fanta or Cola plastic bottles; my father sends them to me whenever an opportunity arises, he buys them from the market-women in Šibenik or Split, I then decant them into dark green mineral water bottles.

My father has smuggled quite a few goods across EU borders for that matter: an octopus, for instance, which was taken out of the ice in Dalmatia in the early morning, arriving in Westphalia the next day thawed just on time, because you either have to beat an octopus after the catch against the quay wall for a sufficient amount of time, or – since the beginning of the technical era – you have to freeze it, in order to get it soft enough for an octopus salad. There was also a leg of smoked ham with very little meat left on it, together with a little pouch of pinto beans, which my father – hardly out of the car – set up for a pašta-fažol, a bean-pasta stew, originally known under the Italian name of pasta e fagioli, a fact which would have merely roused my father to indignation, so I have never brought it to his notice.  This dish can only be a success, if one has a ham shank from the Drniš region for the stock at one's disposal. The number of hams from Drniš is now somewhat limited, particularly since Ratko Mladić was given his general’s rank for certain services in - of all places! - this region, before moving on to Bosnia and Herzegovina; this time, therefore, my father brought along for me not a whole ham, but merely the bone.

This dish can only be a success, if one has a ham shank from the Drniš region for the stock at one's disposal. The number of hams from Drniš is now somewhat limited, particularly since Ratko Mladić was given his general’s rank for certain services in - of all places! - this region, before moving on to Bosnia and Herzegovina; this time, therefore, my father brought along for me not a whole ham, but merely the bone.

While I was studying in Italy, he once had had a portion of cooked chard with potato cubes, seasoned with olive oil and a hint of black pepper transported by ferry to Ancona and then on to Rome by train. Upon arrival of the meal in my Roman room on an April evening, the bearer of this present told me that my father, confronted with her remark olive oil and chard, let alone potatoes, were really to be found in Rome as well, had replied dryly: “But not such.”

He transported smoked sausages from Vrlika, fresh, round pieces of cheese, reminding me of Mozzarella, a remark he dismissed with a disdainful gesture declaring Mozzarella would taste like soap, he sent almonds, walnuts, pears, anchovies, milk-fermented cabbages, indispensable for cooking sarma, a dish originating undoubtedly in the Turkish dolma – but how can the foreign origin stand up to our indigenous refinement!

He transported smoked sausages from Vrlika, fresh, round pieces of cheese, reminding me of Mozzarella, a remark he dismissed with a disdainful gesture declaring Mozzarella would taste like soap, he sent almonds, walnuts, pears, anchovies, milk-fermented cabbages, indispensable for cooking sarma, a dish originating undoubtedly in the Turkish dolma – but how can the foreign origin stand up to our indigenous refinement!

When the news of mad cow disease in Europe had also made it to my town of birth, my father called, asking worriedly, whether I thought a pilot flying from Split to Düsseldorf would be prepared – of course for some remuneration, and if he, an old man, asked very politely – to take some thinly cut schnitzels with him to Germany? His brother had just slaughtered a calf, and because I would become either poisoned, crazy or anaemic in Europe in the long run anyway, these little schnitzels from a healthy calf could at least save me for the time being. If the pilot had no objections, he would bring small, suitably packaged portions of meat to him at the airport once a week, but then again, good calves being rare, so my father, he would surely be able to find something regularly, whether pig, veal or lamb, it would always be of the best quality, he could also get hold of decent chickens and naturally of fresh eggs, too, he would happily assemble a packet respectively for the pilot as well, needless to say that he would meet the pilot’s goodwill with his own. I would just have to drive the 120 km to the airport and receive his consignments there.

Luckily, I could talk him out of the idea, by mentioning with great regret my doubts regarding the flexibility of today’s Croatian pilots, a completely different breed compared to the good old Yugo-bus drivers, who transport guest workers back and forth for days.

Luckily, I could talk him out of the idea, by mentioning with great regret my doubts regarding the flexibility of today’s Croatian pilots, a completely different breed compared to the good old Yugo-bus drivers, who transport guest workers back and forth for days.

Quite often, his consignments ended up in the rubbish. The smoked ribs exuded an unpleasant odour, moths flew up from the flour, it dripped out of badly closed containers and stank of fish, the mussels showed dark discolourations in their sagging yellow flesh, the homemade wine tasted of every heat wave and all the shaking it had been exposed to in the car boot. Only the spirits and oils remained unharmed by transport.

Now, there opened up the prospect of an oil production of my own!

Translated into English by Trude Stegmann